Anemone with hermit crab – on display at The Deep exhibition at the ArtScience Museum, Marina Bay Sands Singapore. The exhibition opened in early June 2015 and will be on till 27 October 2015. According to the explanation that came with this exhibit, these anemones are always with hermit crabs and it is still not known how their relationship begins. What is know though, is that the anemone Epizoanthus, a colony of several organisms, gains from the movement of its host – the hermit crab, from being a sedentary animal to one that is mobile which then increases its chances of finding food. Photo: © TANG Portfolio. 2015 ArtScience Museum. Image taken with a Leica D-Lux 5

While you may know that the oceans cover 71% of the Earth’s surface, are you aware that it contains around 97% of our planet’s water?

Do you also know that 95% of our oceans remain unexplored?

Or, that more men have landed on the Moon than those that have dived into the deepest areas of our oceans?

The point is, we have not fully understood the undersea life in our oceans. For example, scientists do not have the answer as to how anemones establish its relationships with hermit crabs, even though they have clues as to why the two are found together (as seen in the image above).

The huge 6.3-metre long or 20-feet basking shark caught by a trawler off southwestern Australia recently in June 2015 that made international news is yet another fine example of how little we understand about what is in our seas.

The basking shark, with the scientific name Cetorhinus maximus, is the world’s second largest fish. Second only to the whale shark, the last basking shark caught off Australia was in the 1930s or more than 80 years ago. Australia’s Museum Victoria notes that this was just the third sighting in the region in 160 years.

This “accidental” catch, donated to Museum Victoria, will aid scientists in their research into the shark such as its genetics and diet.

According to a June 2015 report by National Geographic, basking sharks will occasionally be spotted at the surface, filtering out small prey like copepods and shrimps. However, as such surface prey is scarce, the basking sharks will dive deep down to 1,000 metres or 3,280 feet where they stay for long periods.

Speaking of going in deep, for those curious about what our oceans hold and wish to find out more, The Deep exhibition, curated by Claire Nouvian and currently held at ArtScience Museum in Marina Bay Sands Singapore till 27 October 2015, is therefore a place to spend some time in and to literally soak up what it offers.

![Radiolarians or Tuscaridium cygneum are members of the zooplankton. These unicellular organisms of around 1.2 cm are found between 400 metres and 2,200 metres deep. They cannot swim but float in the deep water column and sometimes form spherical colonies armed with spines as seen above. When disturbed, Tuscaridium cygneum produce a bioluminescent glow. They feed on phytoplankton and animal prey such as copepods, jellies and gelatinous creatures. [Source: The Deep by Claire Nouvian.] Photo: © TANG Portfolio. The Deep 2015 ArtScience Museum. Image taken with a Leica D-Lux 5](http://www.timewerke.com/testsite/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/The-Deep-Radiolarians-TimeWerke-04.jpg)

Radiolarians or Tuscaridium cygneum are members of the zooplankton. These unicellular organisms of around 1.2 cm are found between 400 metres and 2,200 metres deep. They cannot swim but float in the deep water column and sometimes form spherical colonies armed with spines as seen above. When disturbed, Tuscaridium cygneum produce a bioluminescent glow. They feed on phytoplankton and animal prey such as copepods, jellies and gelatinous creatures. [Source: The Deep by Claire Nouvian.] Photo: © TANG Portfolio. The Deep 2015 ArtScience Museum. Image taken with a Leica D-Lux 5

You can easily see how tall mountains are, such as the Matterhorn in Zermatt, Switzerland that is 4,478 metres or 14,692 feet above sea-level. The first successful ascent on this famous Swiss mountain, by the way, was on 14 July 1865 or 150 years to the day. (The day this article was written, 14 July 2015, therefore marks the 150th anniversary of the first ascent on the Matterhorn).

However, it would be difficult to visualise how deep 4,000 metres under the sea can be, let alone have a perception of what life forms can be found in such a harsh and dark environment.

If you are below 300 metres, you may not even be able to see your hand in front of your face. It is also quite impossible to detect even a photon of sunlight at the depth of 1,000 metres.

That is why exhibitions like The Deep are needed. Firstly, the more than 40 exhibits were once real deep-sea creatures. Though now lifeless, they have been painstakingly put up on display in as realistic a form as possible.

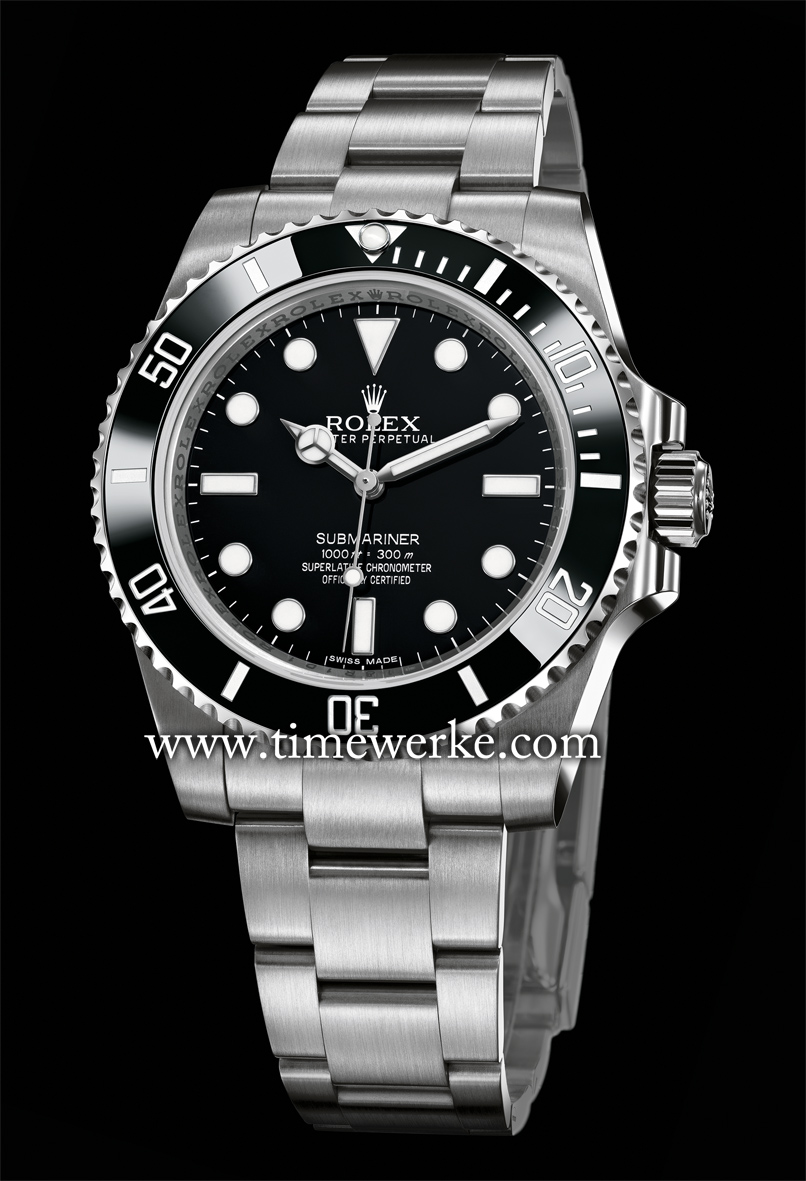

Claire Nouvian, curator of The Deep exhibition which is currently held at the ArtScience Museum in Marina Bay Sands Singapore. She is also behind the book of the same name, The Deep, which we highly recommend as it is a rich resource for those who wish to learn more about sea life in the deep oceans. Nouvian is also the president and founder of the non-profit organization, Bloom Association. Based in Paris and Hong Kong, Bloom Association is an institution that advocates the protection of the ocean’s fragile ecosystem and is against destructive fishing practices. Nouvian lectures on topics such as sustainable development and deep-sea fisheries at universities around the world. We could not help but notice the Rolex which appears to be a Submariner. Photo: © TANG Portfolio. The Deep 2015 ArtScience Museum

“The deep sea is pretty empty if you compare it with a jungle,” concedes curator Claire Nouvian. “The animals [down there] are quite small. There is actually a huge biodiversity but not a huge biomass. After encountering them, you will realise that there are things that can live under any conditions on Earth.”

Secondly, the majority of us will not have the opportunity to descend below 1,000 metres in specially-built submersibles. There are currently less than ten scientific submersibles with the capability to descend to depths of more than 1,000 metres.

James Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger submersible is one such fine example and it took this filmmaker down for a solo dive to 10,908 metres or 35,787 feet.

Moreover, the idea of deep-sea tourism hasn’t quite caught on unlike space tourism. Perhaps it is time to start deep-sea tourism with part of the revenues generated being used for more conservation-related efforts.

![The giant isopod or Bathynomus kensleyi grows to around 40 cm (such as the one seen above and an exhibit at The Deep) and can be found at depths between 310 and 2,140 metres. There are thousands of isopods and the largest known ones live deep down in the sea. As predators of isopods in the deep are rare, they can grow much larger than their surface peers. This phenomenon is known as abyssal gigantism. [Source: The Deep by Claire Nouvian.] Photo: © TANG Portfolio. The Deep 2015 ArtScience Museum](http://www.timewerke.com/testsite/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/The-Deep-TimeWerke-03.jpg)

The giant isopod or Bathynomus kensleyi grows to around 40 cm (such as the one seen above and an exhibit at The Deep) and can be found at depths between 310 and 2,140 metres. There are thousands of isopods and the largest known ones live deep down in the sea. As predators of isopods in the deep are rare, they can grow much larger than their surface peers. This phenomenon is known as abyssal gigantism. [Source: The Deep by Claire Nouvian.] Photo: © TANG Portfolio. The Deep 2015 ArtScience Museum

At this point, we apologise for not bringing up the exceptions. The Rolex Deepsea Reference 116660 is practical for those who embark on regular deep-sea dives around the world. They can be assured that this Rolex will survive even when strapped on the outside of the submersible that descends to great depths.

Why? The average depth of the oceans is 3,729 metres. The water-resistance of the Rolex Deepsea is equivalent to pressure at the depth of 3,900 metres.

Even if you do not make such underwater descents, it is understandable if you make a dive for the Rolex Deepsea as it does have pleasing sporty looks. Better yet, make it a statement piece – a mark of respect for our deep-seas and the need for the preservation of our natural resources.

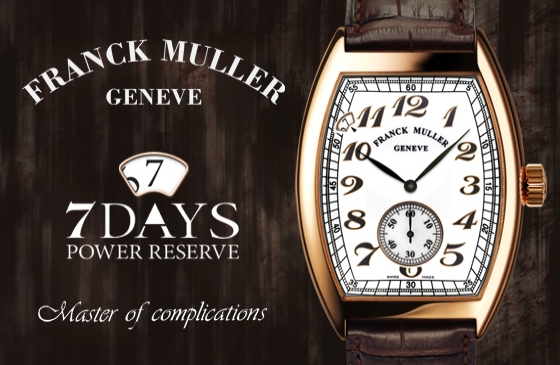

If the Rolex Deepsea is not for you, the Rolex Submariner Reference 114060 introduced in 2012 without the date display and water-resistant to 300 metres will do just fine. Rolex, by the way, was also associated with The Deep travelling exhibitions. The Deep exhibition had premiered in Paris at the Natural History Museum in 2007.

When James Cameron descended deep down in March 2012, the images and samples collected resulted in the identification of at least 68 new deep-sea species.

These specimens included shrimp-like creatures known as amphipods, sea cucumbers, microbes and stringy rock coatings known as microbial mats which house organisms that are able to survive in darkness.

To have a better appreciation of what lifeforms exist at such depths and perhaps what Cameron saw, The Deep exhibition is what we would recommend. “Come see some real animals as though you’ve almost dived deep down,” says Nouvian.

The Rolex Submariner Reference 114060 (introduced in 2012) is one watch you cannot go wrong with whether for daily use or for travelling and water-related sporting activities. This 40mm Submariner in steel features the Calibre 3130 automatic movement and has a unidirectional bezel with the black Cerachrom insert with engraved numerals coated with platinum through magnetron sputtering. It is water-resistant to 300 metres or 1,000 feet, more than sufficient for you to enjoy your recreational dives without any problems. Photo: © Rolex